Ottuk

Chapter Two

In the winter of 2021 I began working on a story about the village of Ottuk, deep in the Tien Shan mountains of Central Kyrgyzstan. The small village of shepherds had been suffering from rampant wolf attacks on livestock which was costing the inhabitants up to 40% of their income each year. I published this story in volume seven of Modern Huntsman. Since then I have returned every year, learning more about the village’s history and culture and becoming very close to the villagers who became my dear friends. The following story recounts my latest trip in the Spring of 2023.

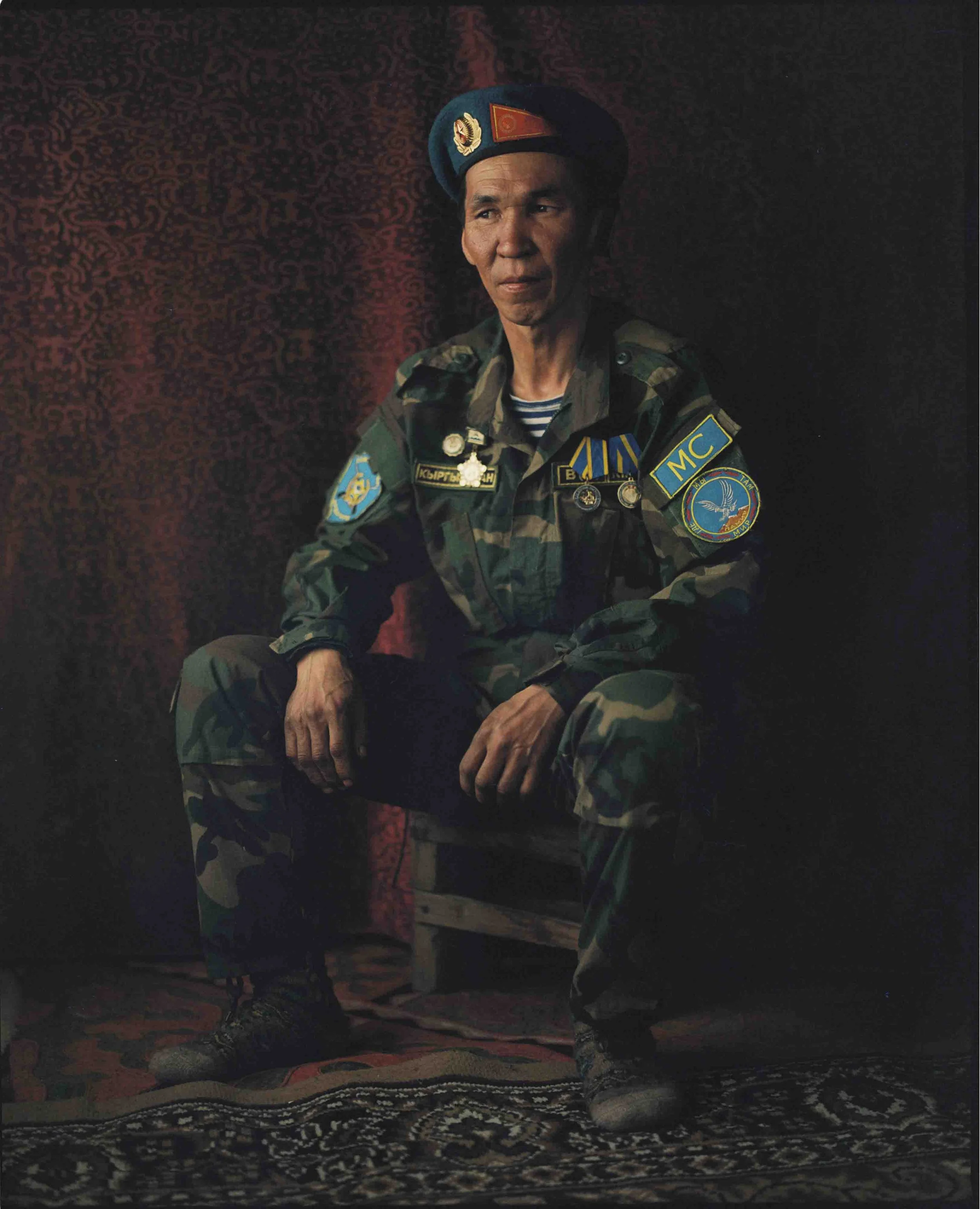

My fixer Chyngyz and I sat quietly in the large living room filled with the traditional foods and fine tableware laid out during periods of mourning. Trembling hands presented Ishimbek’s portrait to us. “You took this photo.” Said Gulnar. “Yes. We spent a lot of time together in those mountains.” I replied. She nodded and tears poured from her red eyes. A sob was held within her, waiting to escape as soon as her two guests would leave. I wanted to hug her but that would not be permitted; she was not family. I asked Gulnar’s son to take us to her husband’s grave, so that she could cry without embarrassment. Leaving the house we were immediately swallowed by the oppressive heat. I glanced at the ledge overlooking Ottuk where I had photographed Ishimbek three years before, unable to believe that he was gone. Ishimbek Ata was one of the first hunters I met in Ottuk. For the past three winters I had been accompanying him and the other villagers on their wolf hunts in the surrounding mountains. One month ago, Ishimbek had suddenly become sick and died, the prognosis was liver cancer. It was he who first told me about the wolf attacks that had been plaguing the village.

“It all began in 1987. The Soviet government introduced Russian Wolves to help clean up dead livestock. They were bigger and more aggressive. They mated with our wolves and the new hybrid produces litters of six to seven pups. Our native wolves produced only half of that. Within three years it was a problem. The wolves were eating up to a hundred horses a year and countless other livestock. We wanted to hunt the wolves like our grandfathers had but they were protected by the government. When the USSR collapsed we were finally able to do something about it and in 92’ we organized the men in the village and started hunting them.”

These were Ishimbek’s words that sparked my imagination on the first night we met, the words which kept me returning to the village and ultimately brought me here, to the dirt path that wound uphill to the graveyard above his house. “Here.” His son said matter of factly pointing at an unmarked pile of dirt. It was the most recent addition to a centuries old cemetery whose minarets and crescent moons undulated in perfect harmony with the mountains in the distance. I crossed my arms, bowed my head and brought Ishimbek into my mind’s eye. I heard his laugh, stared into his ancient eyes and reminisced about the long cold hunts we had braved together. “You’ve had a long, beautiful, hard life. The life of a real man. A life worth living. Thank you for knowing me and for letting me know you. Rest well.” I placed my hand on the top soil and felt the sun beat down on his little patch of earth. Chyngyz placed his hand on my shoulder. “I will recite the Quran now, brother.” We squatted, face in palms and listened to the haunting surah float through the wind. By some miracle the jeep started and we made our way back to Bishkek. With Chyngyz behind the wheel, Ottuk and her mountains passed by us as her memories and legends passed through my mind.

The village elders often spoke of the old days, before the soviet union, when Kyrgyzstan was subject to the Czars of the Russian Empire. Food was scarce and to have shoes was to be rich. The Kyrgyz were still mostly nomadic and contact with Russians was sporadic and rare.

Then came the Bolsheviks and with them came communism, forced collectivization and settlement. Under Stalin there were famines and purges on a biblical scale, forced relocations and the Russification of millennia-old cultures. But, in the second half of the twentieth century the Soviet Union was able to consistently provide food and education at an unprecedented rate. The villages in Kyrgyzstan went from odd collections of yurts to clay brick houses surrounding schools. Finally, in 1991 it all came crumbling down with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Kyrgyzstan suffered greatly once again. Throughout all of these changes one thing remained the same, the wolves.

“The wolves were always a problem.”, said Tokush. She was 92, making her the eldest woman in Ottuk. She spoke slowly and deliberately, ignoring questions she deemed uninteresting and speaking at length about the memories dear to her. “During collectivization our family managed forty sheep. We would smoke them out, make scarecrows and sometimes shoot them…it was never enough.” She recalled when wolves came into her house. They tore up everything. A local hunter scared them off. It was an act of desperation by young wolves looking for food in a time of scarcity. This was during the early nineties when Kyrgyzstan was still recuperating from the fall of the Soviet Union. Deliveries of feed and hay from Uzbekistan had ceased and many livestock died. The wolves were willing to do anything to survive. It was during this time that villagers were being attacked at night on their way to their outhouses. These instances, although quite rare, left an unforgettable impression about the wolves, that they were somehow different than they used to be.

Kyrgyzstan is a land of legends, equally shaped by mythology and experience. In fact, the two are often inseparable. The Kai-beren, a magical mountain goat that once punished a greedy hunter by making him shoot his own son before burying them both in an avalanche, still incites caution in local hunters when choosing their prey. Members of the Bugu tribe refuse to hunt deer out of respect for their ungulate ancestry. For according to legend, a mother deer saved a pair of orphans and brought them to the shores of Lake Issyk Kul where they would go on to found their first village. These legends are innumerable and seldom written down. They were told to me on mountain passes, in jeeps crossing endless stretches of plateau, or in remote villages over cups of tea. The core of these stories was always the same, and no matter how much the details changed from one raconteur to the next, they were always stated as fact. I wanted to separate the fact from the fiction. How much truth was there in the Soviet wolf hybrid story? We pulled into Bishkek just before sunset. The following morning I would have a meeting with the one man who could answer this question.

Kuban Jumabaev, the regional head of the Snow Leopard Foundation, worked out of a small office strewn with innumerable reconyx trail cameras, batteries and file cabinets with a wall covered with framed images of Snow Leopards each bearing very human names. Over his twenty years working for the Foundation he and his small team had helped establish nature reserves throughout the country. Central to their work was documenting attacks on livestock and the near impossible task of quantifying predator populations. Without radio tracking collars his team had only trail camera footage and reports of sightings to go off of but this could only provide a ballpark estimate. Meanwhile the government was releasing estimates that seemed entirely fictitious.

“The government was saying about 3,000 to 3,500 wolves maybe, but I don't know how they did this census.”, Kuban sighed. “There is no good method of counting wolves here. But I think 3,500 is too big of a number. Maybe we have 800 wolves. Maybe 600 wolves. But we don't know. You know wolves, they can cover very large and very long distances in a single night. Like 70 kilometers easily. If there are four or five hunting concessions within these 70 kilometers, they will all report about this wolf…it will become a report about five wolves.”

The inflated estimate of the wolf population had spread throughout the country via news reports and social media. On top of this, wolf attacks were increasing over the past 10 years, but as Kuban explained it was not because there were more wolves; there was more livestock and less natural prey. Over hunting of ungulates by both foreigners and locals alike forced the wolves to dine on the guileless sheep, goats and the occasional horse. Overhunting had become such a problem throughout the country that a moratorium on hunting ibex had just been announced. But for the shepherd in the mountains, more dead sheep simply meant more wolves…wolves believed to be unnaturally aggressive and fecund abominations from soviet intervention. But what about this belief? Surely Kuban would know its veracity.

“The hybrid wolf story, it’s just a legend.”, Kuban laughed with a beaming smile. “I can say that Kyrgyzstan is filled with myths that people really believe. Sometime in the Seventies or eighties the USSR tried to see if African wild dogs would survive in one of our parks. Rumors about this spread and overtime it became a story about Russian wolves being imported. The experiment was a failure. In the Soviet times, all herders had support from the government. They all had pre- approved corrals everywhere and they had their own transport to move from corral to corral. And the Soviet government, they used to limit the number of livestock and also show where to graze livestock. So they had winter pastures and summer pastures…and everywhere they had good corrals. After the Soviet Union, they destroyed all of these corrals to get construction materials. And now they don't want to spend their own money to build good corrals. So the livestock are always outside and vulnerable.”

In other words, the wolf problem was actually a livestock management problem. Although there had always been attacks on sheep and cattle, without the corral system they had gotten much worse. This, paired with overhunting of the natural prey of the wolves, had increased the attacks on livestock. Fortunately, Kuban had been traveling throughout the country not only educating villagers about the dynamics of the wolf problem but also helping them build corrals paid for by foreign donations. These initiatives accompanied with ecotourism promised a resolution that would mitigate losses in livestock and prevent the extermination of the wolves. Home-stays were being developed and tourists were coming to see the snow leopards, wolves and argali in some of the most remote corners of the country. Little by little they were slowly changing people’s attitudes about these animals; they were assets, not liabilities. I decided then and there to visit their most remote partnering village, Ak-Shyrak, some four hours outside of the Sary- Chat nature reserve. It was a place that encapsulated the entire situation, where shepherds, poachers and tourists all came together. A place where I would encounter what Kuban considered the biggest threat to wildlife conservation…mining.

Early the next morning Chyngyz and I loaded up his jeep and headed East. Our first day of driving for seven hours got us half way there, to the village of Barskoon on the shores of Lake Issyk Kul. The 2,408 square-mile lake was a giant blue eye on a brown landscape. Since ancient times this village had been an important silk road caravan stop, a respite from either the steppe, the mountains or the deserts which sat beside it. To the north was the great Kazakh steppe and to the south the towering Eastern Tien Shan, the highest segment of the mountain chain and home to its tallest peak Jengish Chokusu. At 24,406 this mountain feet absolutely dwarfed its neighboring summits. That night, as Chyngyz and I sipped tea in the village, we looked up into that white curtain of mountains and wondered out loud if we would make it all the way to Ak-Shyrak. We had over 150 kilometers off-roading ahead of us and as soon as we left Barskoon there would be no other village, mechanic, gas station or any other sign of civilization until we reached our destination. We had what we hoped was enough extra gas and a single spare tire. “God loves us, we’ll be ok.”, said Chyngyz. “Make sure to pray tomorrow morning. I wouldn’t want him to be angry at us.” I joked.

The road up the Barskoon valley into the mountains was a feet of engineering. Big enough to fit two lorries side by side it snaked up seemingly insurmountable passes. It had been built by the Canadian mining companies and was a small investment for the countless tonnes of Gold and other precious metals it was designed to carry out of the country and into the global economy. As we made our steady progress over the first pass we noticed that the overburdened trucks coming down were Chinese, not Canadian. “Xi Jing Ping has been putting in a lot of work around here.” Said Chyngyz. He surmised that one could tell who was winning the Great Game of the 21st century by which nation’s mining trucks were more frequent.

An hour after the last mountain pass the impressive road had become nothing more than two muddy tracks scarring the landscape across an endless plateau. The air was thin and the jeep felt it as much as we did. In all directions there was nothing but rocks and tundra. A spec appeared off in the distance and slowly revealed itself as the last border outpost. The small brick building was manned by two soldiers who could have been anywhere between twenty and forty years old. Their stint in the mountains had beaten them into premature aging. As they asked for our papers the vodka on their breath explained the redness of their faces; they were drunk, not sunburned. “Where are you going?”, asked the more disheveled of the two. “Ak-Shyrak.”, I answered. “How much further is it?”, asked Chyngyz. “One hundred kilometers”, he replied. “No, further than that.”, mumbled the other soldier. “A lot further. I don’t know how many kilometers. You’ll get there by sundown”. Distance is measured in time in this part of the world. They returned our papers and Chyngyz and I got back into the car. We were confident that we had enough gas to reach the village and then the nature reserve the following day and still be able to make it back to Barskoon… but we didn’t actually know for sure. We discussed between ourselves for a few minutes and finally decided to go for it. “Worst case scenario, we get stranded in Ak-Shyrak and then we’ll just live there.”, Chyngyz laughed.

Many boys from Ottuk end up in frontier posts like this one. Some poured cement hovel over a day’s journey away from everything they have ever known, certainly further away than anywhere else they have ever traveled. Nadir, my best friend in Ottuk, recently told me that his eldest son would be joining the border guards. He was eighteen which meant that he would soon be married as well. I imagined how his life would unfold from then on. Would he be stationed in a location as remote as this one, or would he perhaps be in a high traffic town on the Kazakh or Uzbek border? It’s doubtful he would ever return to live in Ottuk. His wife will be pregnant, he’ll have cash for a simple apartment in Bishkek, Osh or some other city. He’ll chase promotions, develop a side hustle in an urban center and slowly settle into a seated bureaucratic position in a stuffy government building with only the scars on his hands to remind him of the calluses he once earned through farm work and wolf hunting. Another young man who left the village for a “better life”, making his father proud while simultaneously abandoning tradition.

As the sun was creeping behind the mountains we reached the village. It consisted of a single road with about 10 houses on either side. We found the home-stay Kuban had arranged for us and met Joldosh, the park ranger who would take us to the reserve the following morning. He was a squat man with an unmistakably kind face that matched the topography of his environment. “Tonight we eat and sleep. Tomorrow we have a lot of traveling to do.”, he smiled with gold teeth and beckoned us inside. Over tea and a simple dinner of noodles with horse meat, the conversation soon turned to the nearby copper mine. ‘All the people here know that the mine is bad for the environment. But it’s good money and stable employment. Even some rangers have left to work for the mine.’, Joldosh lamented. ‘Shepherding is very hard, especially up here, but it’s our culture. Without shepherding Kyrgyz culture will not survive. It’s too central to us.’ On the small television behind Chyngyz a semicircle of musicians were singing ancient ballads from a distant nomadic past. For several minutes at a time we would listen to a different musician’s monotone chanting as they plucked dissident notes on their Komuz, the three stringed fretless lute which is the national instrument of Kyrgyzstan. They were not singing, they were telling stories, stories that had changed from generation to generation for thousands of years. Haunting lamentations about love, death, and mountains. The eerie melodies and meditative voices seemed as natural to the landscape as the sound of the wind that was howling outside. “Perhaps one day they will be singing about hybrid Russian wolves.”, I thought to myself.

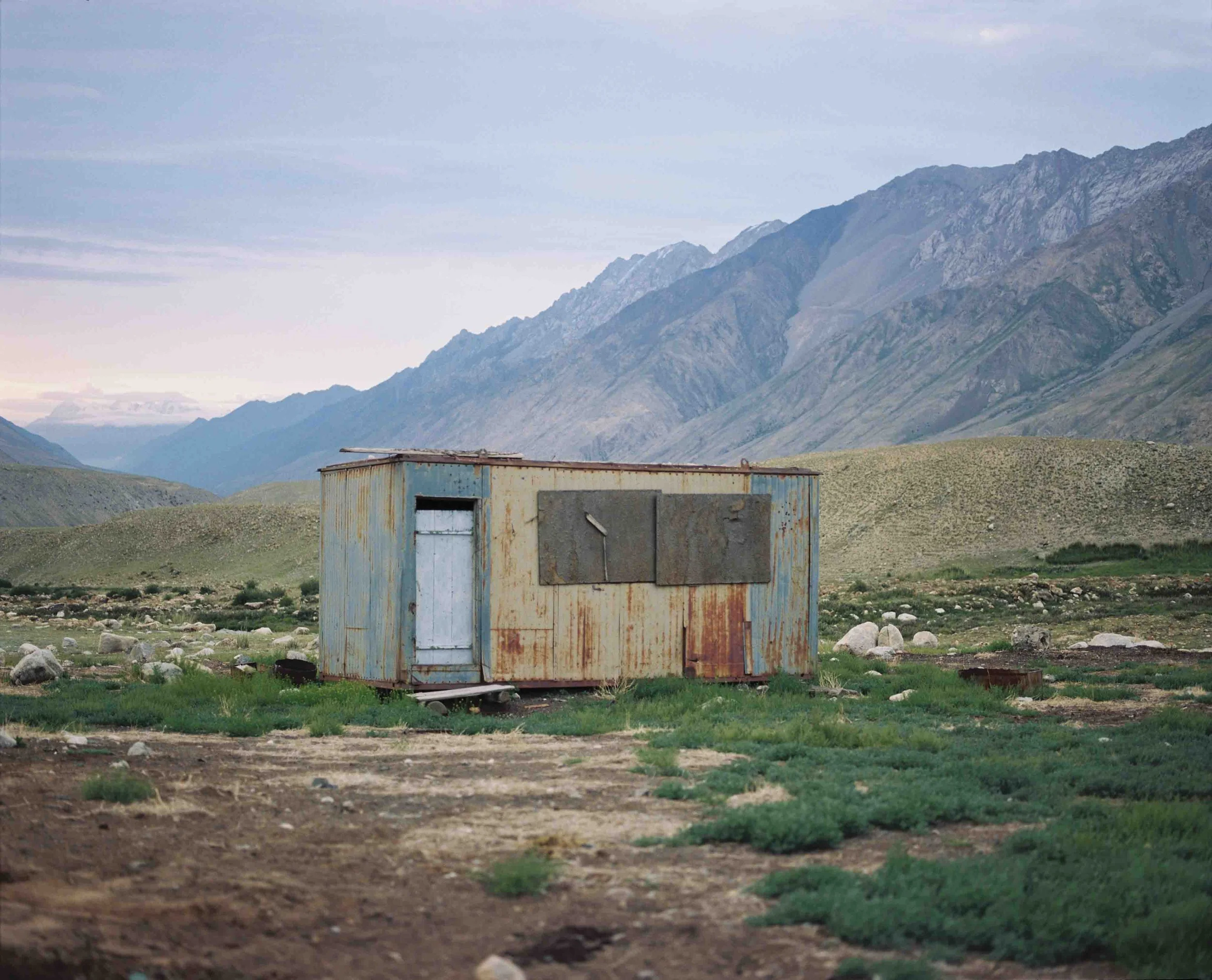

We left Ak-Shyrak just after sunrise. For five hours we drove through high plateaus. There were no roads, only paths of least resistance, and more than once we had to stop and navigate around impassable terrain. Our journey brought us to a rocky valley surrounded by forbidding mountains. “Right here.”, said Joldosh, pointing to a lonely little hut. “This is the outpost where we’ll be staying.” Inside was a camp stove and a raised platform to sleep on. Hanging from the ceiling were bags of dried goods and canned meat. The claustrophobic proportions of our temporary home made the expanse of the high plateau outside even more impactful. There was simply nothing around apart from the occasional eagle and the ever present drone of the wind. I felt as though I were either the first or last living being on Earth, separated by countless millennia from the world of people. In such a stark landscape concepts of governments, markets, cultures and society seemed too abstract to fully comprehend. There was only the heat of the sun and the coldness of its absence. Despite this feeling of total disconnection from the modern world, this region was a hotbed of geopolitical competition. For just on the other side of the mountains was Xinjiang, China’s far western province. The Chinese had been mining in this region of Kyrgyzstan for many years and very soon they would be building a highway not too far from this valley to facilitate the extraction of ore. The Russians, Canadians and Americans had their own plans for dominating the mining industry here and as such, all of them had their own road-building projects. This development had already pushed the snow leopards deeper into the mountains and altered the distribution of their prey. Even this nature reserve was not safe from the tournament of shadows; others like it had already been divided into mining concessions. My heart sank as I noticed the electricity towers some three miles off in the distance. They had not been cabled yet but they would be soon and beneath them would be a new mining road. I wondered if this development would not only remove the wildlife from these mountains, but men like Ishimbek as well.

After several hours of hiking with my camera I returned to the shack. Chyngyz and I cut up onions and halal sausage for dinner. As we filled our stomachs, Joldosh began to tell a story. My heart filled with joy and my eyes watered as I heard the familiar yarn unroll. “It all began in the 80’s, when the Russians brought in wolves to help clean up dead livestock…” I looked out of the window and into the mountains and felt as though Ishimbek were sitting right beside me. Legends preserve not only the memory of a place and time but of the people who tell them as well.